Ecology 🐬🦋🦭

“Everything that we do, from the water we drink, air we breathe and food we eat is all dependent on the natural world. The processes that keep our reservoirs clean and the food in the fields growing are all underpinned by the wildlife - or biodiversity - that surrounds it, and without any of these, other species simply would not be able to survive.

“It is not, however, the mere presence of these species that matters most but their relationships with each other and how they interact to create a complex network of life. As individual species are then pulled from this web, the ecosystem in which they live eventually collapses.” - Natural History Museum report

This is a look at some aquatic and semi-aquatic species, showing theirRiver-water crowfoot (Ranunculus fluitans)

There are several common species of ranunculus found in the rivers and lakes of Britain and Ireland . Above the surface, the leaves of Ranunculus fluitans are very similar to those of other members of the buttercup family, while the submerged leaves are finely divided: characteristic of a truly amphibious plant. The flowers are at their best from mid-May until the end of June.

Slow to moderate paced lowland river reaches of shallow depth, especially where the river bed contains limestone, are places where this lovely water plant is most plentiful. In the wild, Ranunculus fluitans is an important food source for many species of fish and waterfowl. The plant's leaves and stems are eaten by ducks, geese, and other birds, and its seeds provide a source of food for fish and insects. It is also an important part of the aquatic food chain, as it provides essential in-stream habitat for freshwater shrimps, snails, insect larvae and nymphs.

Caddisflies (or sedges - trichoptera)

Insects in the order Trichoptera are commonly known as caddisflies or sedges. There are 199 species of caddisfly in the UK. Caddisfly larvae live underwater, where they make cases by spinning together stones, sand, leaves and twigs with a silk they secrete from glands around the mouth. Most larvae live in these shelters, which can either be fixed or transportable, though a few species are free-swimming and only construct shelters when they’re ready to pupate.

Adult caddisflies are moth-like insects which generally fly at night. They hold their wings above their body in a roof-shape when at rest.

Adults are often attracted to moth traps, or can be found during the day on vegetation near to the water's edge, or flying in swarms over the water. Caddisflies are an important food source for all kinds of predators, including Atlantic Salmon and Brown Trout, and birds such as the Dipper.

Common Barbel (Barbus barbus)

One of England’s native fish species, believed to have been present in at least some English rivers for more than 10,000 years. They are thought to be native to eastern English rivers between Yorkshire and the Thames but have been widely stocked in many other rivers,others, such as the Severn and Wye, and in parts of Scotland.

Barbel are cyprinids and there are several species from the genus Barbus that all share similar anatomical features. These include adaptations to living in faster flowing water, such as a streamlined body with large, almost mini-wing like, pectoral fins and powerful tails. Barbel species also have downward-facing mouths and two pairs (four in total) of barbules (sometimes referred to as barbels or whiskers) on their upper lips, which hint at their preferred benthic feeding habits.

Their underslung mouths make them especially well adapted for feeding on benthic organisms, including crustaceans, insect larvae and molluscs, which they root out from the gravel and stones of the riverbed. Barbel diets change as the fish develop from fry to juveniles and then to adults. Diatoms that cover rocks and the larvae of non-biting midges (Chironomidae) are particularly important foods for young fish. Barbel also like to seek refuge and forage amongst aquatic plants (especially Ranunculus) or underneath overhanging trees or submerged tree roots and branches.

Barbel can live for 20 years and mature relatively slowly, with males taking 3–4 years and females up to 8 years to become sexually mature. This leaves them susceptible to a range of pressures over a prolonged period, which can affect their ability to reproduce successfully and thrive in rivers. Some of the issues facing barbel include poor water quality and predation, at all life stages, from a range of predators, including human poaching, piscivorous birds (e.g., herons, goosanders and cormorants), piscivorous fishes (e.g., pike and perch) and piscivorous mammals such as mink and otters. They also suffer with destruction and modification of habitats, which can create bottlenecks for different life stages – barbel require different habitats throughout their life cycleslives and the juxtaposition of these is important for maintaining viable populations.

Common frog or grass frog (Rana temporaria)

The Common Frog is easily our most recognisable amphibian. They’re found throughout Britain and Ireland, in almost any habitat where suitable breeding ponds are near by. Common Frogs have smooth skin and long legs for jumping away quickly. Garden ponds are extremely important for common frogs, particularly in urban areas.

They breed in shallow water bodies such as puddles, ponds, lakes, and canals. They deposit ‘rafts’ of spawn, often containing up to 2000 eggs. Each small black egg is surrounded by a clear jelly capsule around 1 cm across. Frogspawn is a remarkable material. It is 99.7% water and dissipates heat very slowly, which means that the egg mass is maintained at a higher temperature than the surrounding water. In addition, the egg mass is permeable to water currents, ensuring that all eggs within the mass receive adequate supplies of oxygen. The temperature at which the eggs and emergent tadpoles develop influences the speed of development. Common Frog tadpoles are black when they hatch but develop light bronze speckles as they mature.

Mating and spawning is usual over by the beginning of May (though may be later in more northerly latitudes) and most adults move away from the breeding pond within a few days of mating. By the beginning of August, most of the resulting froglets will have left the breeding pond.

'Mature' tadpoles are faintly speckled with a gold/brown colouration which distinguishes them from the black tadpoles of the common toad. They tend to feed on algae and decomposed plants. They are eaten by a range of aquatic animals, including dragonfly larvae and newts.

![]()

Tadpoles generally take up to sixteen weeks to grow back legs, then front legs before they metamorphose into tiny froglets, ready to leave the water in early summer (often June, but in some ponds this may be as late as September). They become carnivorous once the back legs are grown, taking small prey like mites, ticks and small fly larvae.

Adult males grow up to 9 cm in length and females up to 13 cm in length. They are usually a shade of olive-green or brown (although can be yellow, pink, red, lime-green, cream or black). They have dark patches on the back, stripes on the hind legs, and a dark ‘mask’ behind the eye. Oval, horizontal pupil. Call: soft repetitive croak.

The Common Frog is native to the UK. They are found throughout Britain and Ireland. They are also widespread across Europe but numbers are thought to be declining.

They tend to be most active at night, they are carnivores so feed on a variety of invertebrate prey including slugs and snails which makes them especially popular with gardeners.

Despite their wide mouths, frogs drink by absorbing water through their skin and swallow using their eyes – they retract them into the head to help push food down their throats. When they moult, they usually eat the skin as it is a valuable source of nutrition! During winter they hibernate under rocks, in compost heaps, or underwater, buried in mud and vegetation.

Frogs make attractive meals for a vast array of wildlife, so they are vulnerable to predators on the ground, underwater and from above. Their predators include small mammals, lizards and snakes, water shrews, otters and birds such as herons.

Commom frogs are also threatened by degradation of habitats (the loss of ponds, even garden ponds, as well as lakes), threats to many food sources from declining water quality, and the introduction of disease.

Otter (Lutra lutra)

Otters inhabit rivers and wetland, coastal waters & marshland. They have brown fur, often pale on underside, a long slender body, small ears on a broad head, long thick tail, and webbed feet. An otter swims very low in the water, the head and back barely showing. They are usually 60-80cm, the tail is about 32-56cm. Their weight is on average 8.2kg for males, 6.0kg for females. They live up to 10 years, though few survive more than five.

The otter is a secretive semi-aquatic species which was once widespread in Britain. By the 1970s, otters were restricted mainly to Scotland, especially the islands and the north-west coast, western Wales, parts of East Anglia and the West Country (though they remained common and widespread also in Ireland). This decline was caused by organo-chlorine pesticides. Since these were withdrawn from use, otters have been spreading back into many areas, especially in northern and western England.

Otters eat fish, especially eels and salmonids, and crayfish at certain times of the year. Coastal otters in Shetland eat bottom-living species such as eelpout, rockling, butterfish, as well as crabs an shellfish. Otters occasionally take water birds such as coots, moorhens and ducks. In the spring, frogs are an important food item.

They are an apex predator in Britain and Ireland, even taking mink, and are themselves only at risk in the wild when young, from eagles, or when venturing outside their coastal range and encountering much larger marine predators. Their biggest threat is still from humans, though. Commercial fisherman resent otters taking their catches, while poor river water quality sends otters into stillwater lakes, where they come into conflict with anglers. Road traffic, habitat destruction and fishing nets all take their toll.

Otters can travel over large areas. Some are known to use 20 kilometres or more of river habitat. Otters deposit faeces (known as spraints, with a characteristic sweet musky odour) in prominent places around their ranges. These serve to mark an otter’s range, defending its territory but also helping neighbours keep in social contact with one another. Females with cubs reduce sprainting to avoid detection.

In England and Wales, otter cubs, usually in litters of two or three, can be born at any time of the year. In Shetland and North-west Scotland most births occur in summer. Cubs are normally born in dens, called holts, which can be in a tree root system, a hole in a bank or under a pile of rocks. About 10 weeks elapse before cubs venture out of the holt with their mother, who raises the cubs without help from the male.

Otters are strictly protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) and cannot be killed, kept or sold (even stuffed specimens) except under licence. In the late 1950s and early 1960s otters underwent a sudden and catastrophic decline throughout much of Britain and Europe. The cause was probably the combined effects of pollution and habitat destruction, particularly the drainage of wetlands. Otters require clean rivers with an abundant, varied supply of food and plenty of bank-side vegetation offering secluded sites for their holts. Riversides often lack the appropriate cover for otters to lie up during the day. Such areas can be made more attractive to otters by establishing “otter havens,” where river banks are planted-up and kept free from human disturbance. Marshes may also be very important habitat for raising young and as a source of frogs.

While otters completely disappeared from the rivers of most of central and southern England 50 years ago, their future now looks much brighter. There is evidence that in certain parts of the UK the otter is extending its range and may be increasing locally. However, otter populations in England are very fragmented and the animals breed slowly. Attempts have been made to reintroduce otters to their former haunts by reintroducing captive bred and rehabilitated animals, with some attempts proving very successful.

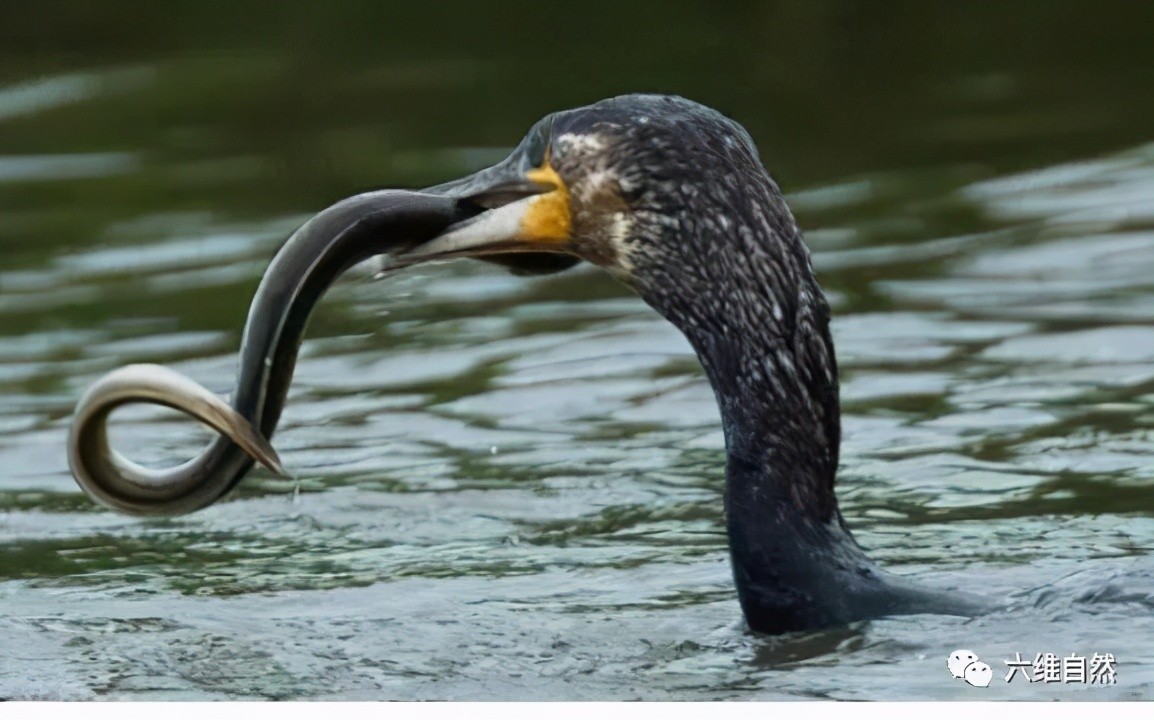

Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo)

There are two subspecies of cormorant in the UK. There's the mostly coastal nesting Phalacrocorax carbo carbo, and there's Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis, which arrived from continental Europe and has led the increase of inland cormorant nesting colonies. This has accounted for a 53 per cent range expansion in Britain since the first nesting by sinensis in 1981 (at Abberton Reservoir, Essex).

By 2005 there were an estimated 2,100 pairs of sinensis nesting in Britain. However, since the establishment of inland tree nesting by sinensis Great Cormorants, coastal birds have also started to breed inland, particularly in those sinensis colonies that are older and well established.

Great cormorants build large conspicuous nests with coastal colonies normally situated on stacks, rocky islets, cliffs or rocky promontories. Many colonies persist at the same location for long periods, but others come and go or suddenly shift location – the presence of a colony in one year is no guarantee that there will be one there the following year. Inland colonies will nest in trees.

The cormorant lays a clutch of three to five eggs that measure 63 by 41 millimetres on average. The eggs are a pale blue or green, sometimes with a white chalky layer covering them. These eggs are incubated for a period of about four weeks.

In marine environments cormorants are found in sheltered coastal areas on estuaries, coastal lagoons and coastal bays, requiring rocky shores, cliffs and islets for nesting, but generally avoiding deep water and rarely extending far offshore. It also inhabits fresh, brackish or saline inland wetlands, including lakes, reservoirs, wide rivers, flood waters, deep marshes with open water, swamps and oxbow lakes, requiring trees, bushes, reedbeds or bare ground for nesting and avoiding overgrown, small, very shallow or very deep waters.

Cormorants forage by diving and capturing prey in their beaks. The duration of dives is around 28 seconds, with the bird diving to depths of about 6 metres. About 60% of dives are to the benthic zone and about 10% are to the pelagic zone, with the rest of the dives being to zones in between the two. Studies suggest that their hearing has evolved for underwater usage, possibly aiding their detection of fish. Cormorants' diet consists predominantly of fish, including flatfish, as well as crustaceans, amphibians, molluscs and nestling birds. At sea the species preys mostly on bottom-dwelling fish, occasionally also taking shoaling fish in deeper water. It is a generalist, having been shown to feed on at least 22 different fish species. They hunt by swimming.

Cormorants are large birds, up to 100cm long. Their wingspan can be 160cm, and they weigh from 2 - 2.5kg. They live on aerage 11 years. Their long necks and hooked bills give them a primitive, almost reptilian, appearance. This is enhanced by the fact that they are commonly seen standing on top of rocks, posts or trees with their wings out-stretched.

The cormorants' oily plumage is only partially waterproof and after diving for fish, they effectively have to hang out their wings to dry.

Many fishermen see in the great cormorant a competitor for fish, which meant it was hunted nearly to extinction in the past. Due to conservation efforts, its numbers increased. At the moment, there are about 65,000 birds in the UK (1.2 million in Europe). Increasing populations have once again brought the cormorant into conflict with fisheries. For example, in Britain, where inland breeding was once uncommon, there are now increasing numbers of birds breeding inland, and many inland fish farms and fisheries now claim to be suffering high losses due to these birds. In the UK each year, some licences are issued to cull specified numbers of cormorants in order to help reduce predation. It might well be that the birds, like the otters, are raiding fishing lakes because of a decline in wild prey in polluted waters.

At sea, due to the species' foraging behaviour (shallow diving) and habit of hunting within purse-seine and gill-nets, the species is particularly susceptible to bycatch.

report</p