How we tick

It is helpful to understand how our nervous system is impacted by stress, strong emotion or perception of danger. We can use this understanding to find more joy, ease and satisfaction in our lives and increase our ability to respond skillfully in challenging situations. As an activist we can experience stress in different situations, such as:

- the stress of taking part in direct action — how will people, including the police, react, what will the legal consequences be?

- through the recognition of crises facing us and the harm we and others are facing;

- through seeing the inaction or denial of the facts, which has become a prominent part of politics and social media;

- through working with other activists who may have different ideas and ways of communicating;

- through not paying attention to our health, work and action boundaries;

- through the stress we put on ourselves by overwork or continuous action.

Stress and our bodies

We are going to take a brief journey into the nervous system.

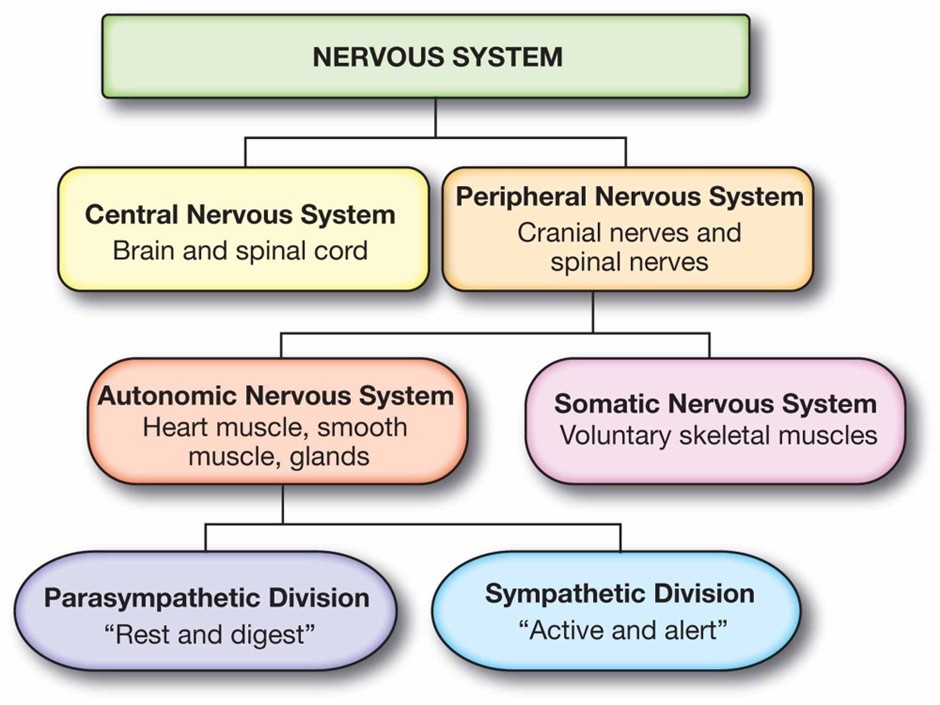

The Central Nervous system, C.N.S (brain and spinal chord) is responsible for receiving, processing and storing incoming sensory material. Once interpreted commands are sent to the peripheral nervous system (P.N.S). Its main role is to relay messages between the Central Nervous System (CNS) and the body’s muscles, organs, and senses.

The Peripheral Nervous System is divided into: the Somatic Nervous System, which controls voluntary movements by carrying sensory information to the CNS and motor commands to skeletal muscles and the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which manages involuntary internal functions like heart rate, digestion, and gland activity.

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

Our nervous system is concerned with identifying whether our environment is safe or not right now. The automatic nervous system plays a key role in this. It is in turn divided into the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic systems. Understanding how these systems work can be very helpful for developing balance and resilience.

Useful theories for working with our autonomic nervous system

There are two theories that have come from work with people suffering from trauma (developmental or post traumatic stress) that can give us some pointers about managing our stress levels.

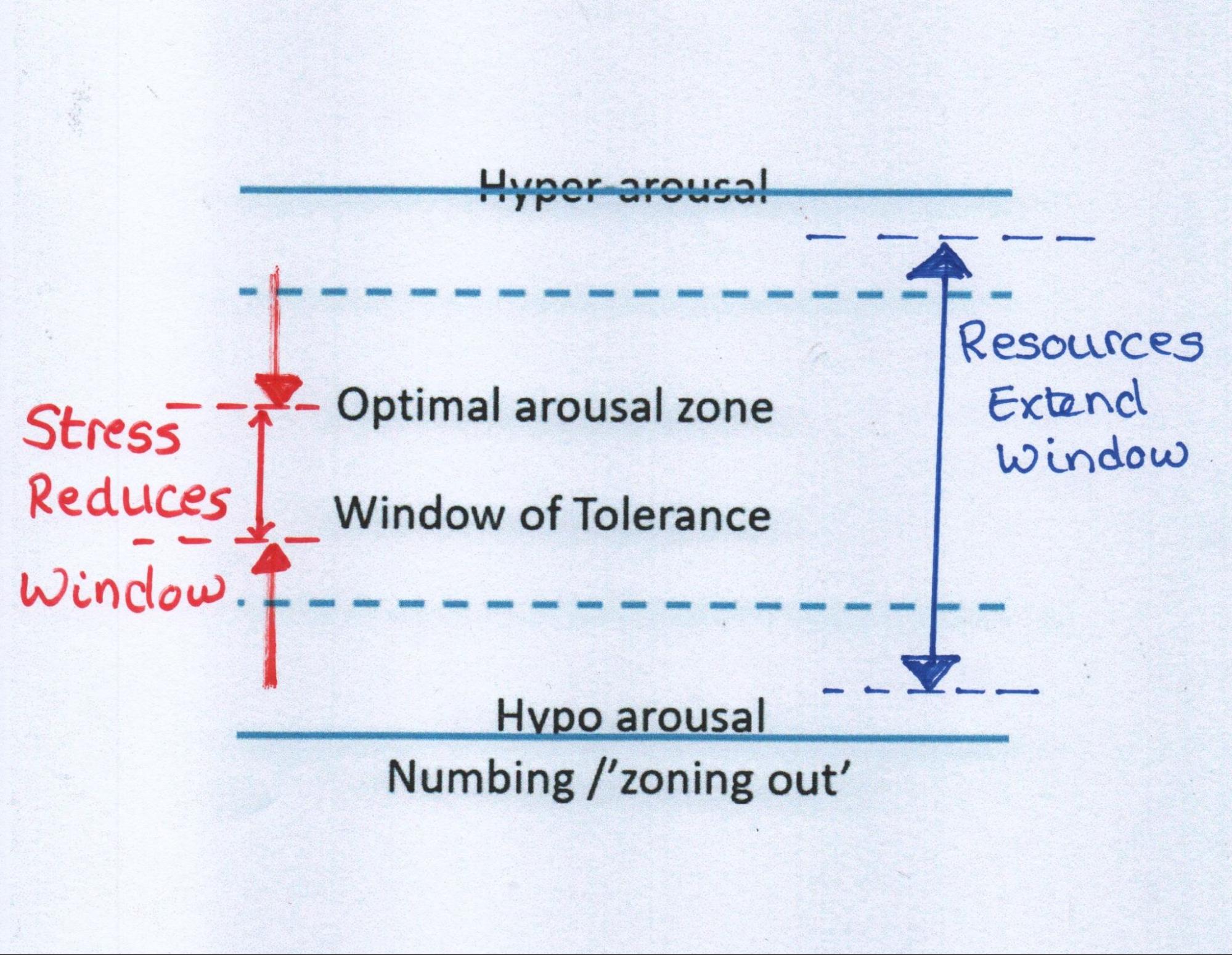

One of these, called the “window of tolerance”, describes a zone where we can manage our experience and emotions in a balanced way.(Dan Siegel) It can be usefully connected to another concept, the polyvagal theory (Stephen Porges). The polyvagal theory helps us understand the role of the Automonic Nervous System (ANS) in balancing our emotional states and in social connection.

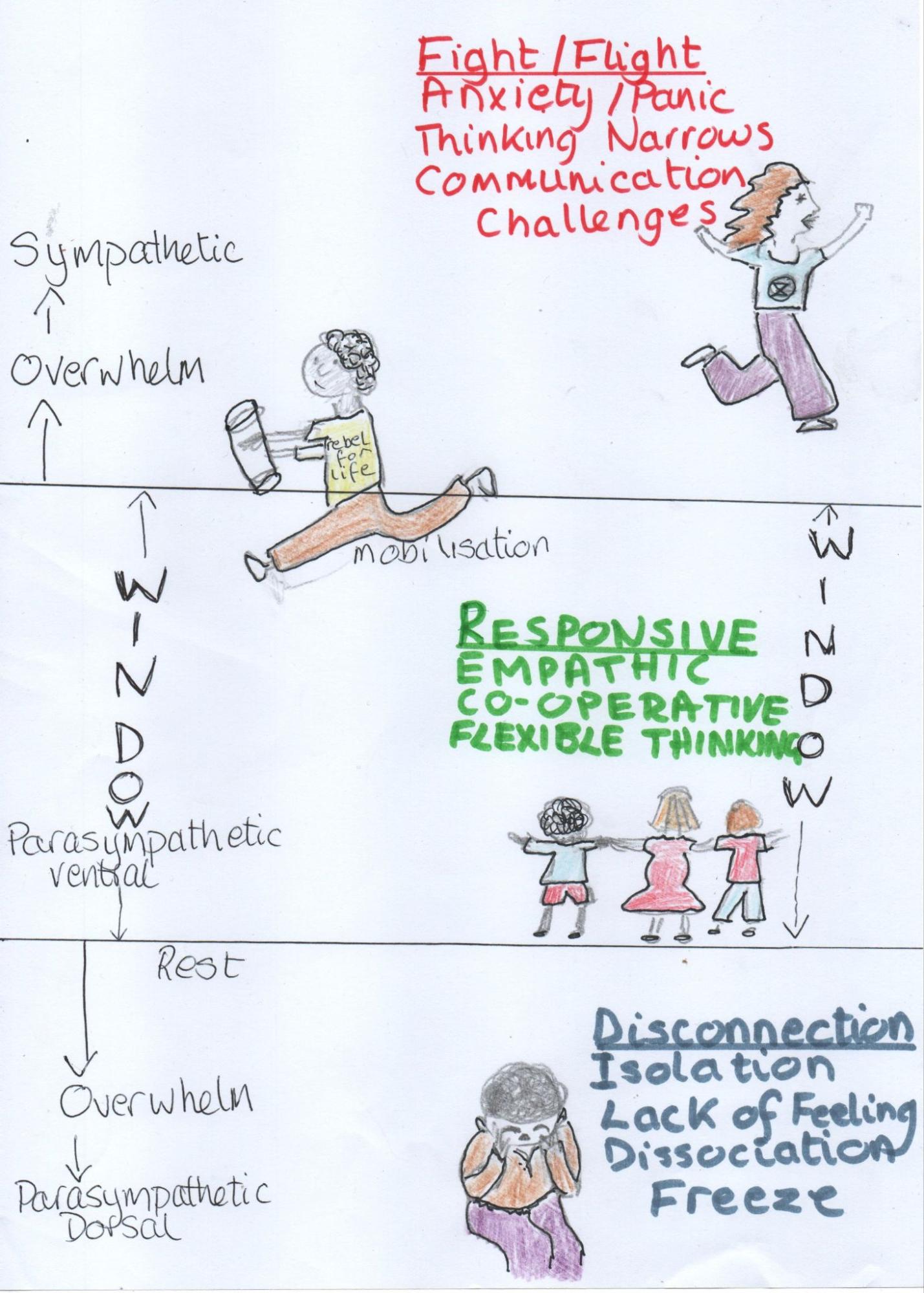

The polyvagal system outlines three basic emotional states:

Combining these two theories — so matching the “window of tolerance” with the social engagement system of Porges polyvagal theory — gives us an understanding of the way our nervous system responds to stress and danger (perceived or real). It also helps us understand how best to take care of ourselves so we can manage challenging situations more easily. See diagram below, the “window of tolerance” being between the dotted lines.

We can begin to be aware when we are moving into states of fight or flight, or into a place of shutdown or freeze, and take steps to wisely support ourselves when this is happening. We can learn to integrate practices and behaviours into our daily lives that support our ability to manage the various challenges that we are faced with. We can also use some of these practices to support our ability to respond wisely and effectively in potential situations of acute threat, e.g. when taking non-violent direct action (NVDA).

Neuroscience has helped us identify particular things that help us move into our “window of tolerance”.

Being with Safe Others

This can mean building up connections and friendships in our daily life. Our nervous systems are soothed by feeling like we belong. These relationships can be with people or other beings.

When taking action it is helpful to be part of an affinity group where everyone can feel confident that they are supporting each other in your different roles. In order to keep this sense of connection, check-ins before action and debriefs post action are really helpful.

Mindful awareness

Using our senses of smell, hearing, taste, sight and our felt sense we can pay attention to what is happening in our experience moment-by-moment. “Coming to our senses” in this way helps move us into a calmer state and helps us move away from ruminative or catastrophising thinking.

Developing or practising “somatic awareness”, such as tuning into our breathing or the sensations in our bodies is a very helpful way to settle ourselves. There are many practices; from yoga and tai chi, breathing exercises and other somatic practices that can help. You can find some of these in the resources section of this doc.

Establishing a mindfulness meditation practice can also be a useful way to calm the nervous system. It is also really helpful in supporting us to understand when and how we get triggered into flight, fright or freeze.

Exercise or movement

Exercise of all kinds from jogging to dancing is very helpful in breaking down the stress hormones and producing endorphins that promote a sense of wellbeing and positive mood. When at a direct action, taking time to move or even just give the body a good shake or shimmy can be a great way to feel calmer.

This is a brief summary of how we can use our understanding of our nervous system to look after ourselves, and you will find much more on this subject with a little research. If you are super interested in this area we would recommend a book on working with trauma called ‘The Body Keeps the Score’ by Bessel van der Kolk.