Decision Making Processes

[Note: this guidance is referred to by Section C.7 of the XR UK Constitution.]

This page includes some basic steps and then details specific decision making processes. It is aimed mainly at facilitators.

These decision making processes are alternatives to Integrative Decision Making (IDM). They can be used in settings where IDM is not required by the Constitution.

A fair process helps to get people on board with a decision that may not be their first choice. If people feel what they care about has been heard and the decision is made for a legitimate reason, they are more likely to accept it and remain engaged with the group. Finding a way to balance a fair process with an efficient one is the fine art of facilitation!

Consent Based Decision Making

The overarching approach we recommend taking to decision making is consent based decision making. Consent based decision making is about finding an option that sits within everyone’s range of tolerance (“OK, I can live with it”), not their range of preference (“I love it”). This is because finding a proposal that everyone loves will be really difficult while finding one that everyone can live with will be a lot easier. Let’s go with a proposal that’s good enough, rather than trying to perfect it. Explain this approach to the group before starting the decision making process.

Tips for before starting the process

It’s good to be clear about the type of decision making process that will be used before the process starts. This way people will set their expectations, for example, whether they will have to accept what the majority wants to do or whether the proposal will be changed based on their concerns. Always state the decision making process and give a brief explanation before starting it. Don't get into endless discussions about what process to use, you should decide how to decide as their competent and confident facilitator.

Most decisions are time-bound, especially during rebellions, so decisions have time limits. Getting clear on the time limit before the meeting and stating it at the start will help the group understand why you’re using a specific decision making process, e.g., “the police will make arrests within 5 minutes, so we’re going to do a majority vote”.

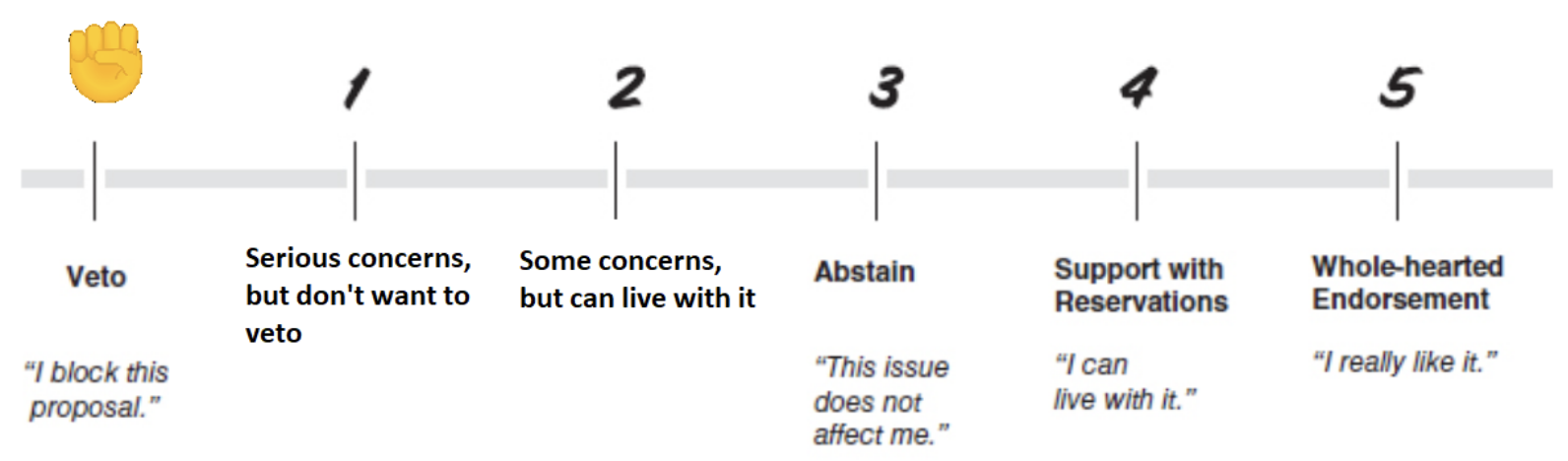

1. Fist to Five

Fist to Five is a decision making process which allows people to state more than yes or no. This is very similar to consent except that people can give more nuanced responses. It’s important to people to be able to express dislike, so we need to give them a way of doing it that's not a block. They can state any of the following options:

Explain the instructions very slowly, maybe even twice. Don’t be rushed yourself or people will feel rushed and they don’t like it.

- Explain the different response options, i.e., the Fist to Five are (“Instead of asking you to vote yes or no, I want you to hold up a number of fingers:

- 5 finger if you really like the proposal

- 4 if you think it’s pretty good

- 3 if you want to abstain (e.g., “I’m indifferent”)

- 2 if you have reservations but can live with it going ahead in order to not hold up the group

- 1 if you have serious concerns, but wouldn’t veto this version of the proposal (see below)

- Fist if you have a major concern that means you want to veto this version of the proposal. It’s very important to make this clear to the group. Vetoing the proposal should be grounded in a reason ( e.g., violating XR UK’s Principles & Values or someone may get hurt due to the proposal), rather than personal preference (e.g., “I just don’t like it”).

- State the threshold at which the proposal will be passed, e.g., “Given that we have 10 more minutes so need to make a decision quickly, the proposal will pass unless someone blocks”. (This sets the threshold for passing the proposal as quite low, so it is quite likely to pass.)

- If there is a veto or serious concern, you can either ask the person voicing it what they would need to amend to pass the proposal.

- Ask the proposal/idea/question and record the number of people for each number. Hopefully, major concerns will have been voiced before this stage, but just before asking people to respond remind them that you do want to hear major concerns if anyone has any because then we can amend the proposal to make it better.

- Alternative option: for a secret ballot you could choose to ask people to close their eyes if they’re comfortable doing so.

- It's useful to check in if you have large quantities of low numbers - if there isn't a block, but everyone is at 1 finger (they have concerns), then you might want to spend more time thinking about this proposal - if you have time. You could say something like "I'm seeing lots of 1s - can I invite one or two people to speak to why they've given this a 1?" Then use that to decide if we need to resolve something before moving forward.

- State the outcome:

- If there is no block (i.e., a fist) and you’re short on time, consider the proposal passed.

- If there’s a block, invite that objector(s) to share their reasons, then work with them and the proposer to amend the proposal and ask people to decide on the new version by showing a number again.

- If you have time, invite those who have expressed serious concerns (1) to share their concerns. If multiple people have serious concerns, it’s worth considering whether to work with the proposer and objector to amend the proposal if possible, as described above.

Pros: Allows for more nuance; people can express that they have a concern but don’t want to block the proposal. Asking for a number can speed things up.

Cons: Need to explain what the numbers mean and people need to remember it so it can be too complicated in time pressured situations. You need to start off with one proposal; this will not work when there are several on the table. Works best with a small group of people, say less than 10.

Thresholds: As the facilitator you can set the threshold; you can declare the decision as passed even if there’s one or two people disagreeing (majority vote situation) or decide to hear from everyone who has a niggling concern. The threshold you choose will depend largely on the time limit and the seriousness of the decision. If people do not agree with the threshold, they will tell you. As a facilitator, it's most important here to keep open and to welcome refinements - not always easy, especially when under pressure.

In the above example, we’ve set the threshold in favour of the proposal passing since it will only be blocked if someone's concerns are so serious they are prepared to veto the proposal. This is deliberate - we want to be biased in favour of taking action and trying things.

However, we also want good proposals, so if you have the time or the decision is very important, consider resolving the issues of those who have serious concerns - the facilitator and group can set the threshold wherever they like.

2. Majority Vote

The group is expected to go with what the majority is in favour of.

- Ask the group to raise their hands if they are in favour of the proposal, against it or abstaining (eyes closed for a secret ballot).

- Record the number voting for each.

- Announce the decision.

Pros: Fast, perfectly fine to use it when a decision needs to be made super rapidly or is inconsequential, e.g., “shall we move to the shade?”. But when the decision will be contentious, Fist to Five would be better. Works well when there are many people. It’s OK to disagree and this method reflects that.

Cons: The minority may be unhappy, feel undervalued and disengage from the group.

3. Temperature Checks

Temperature checks can be seen as a type of voting, but they are usually not taken as a formal decision unless all hands are in the air or the decision is inconsequential (e.g., "should we stay here or move to the shade?”)

- Tell people you’re going to do a temperature check and what the response options are: People do jazz hands in the air for yes, and downward jazz hands for no.

- Ask the question.

- Announce the decision.

Pros: gives a quick idea of how the group feels about something.

Cons: can be ambiguous what it means when people put their hands in the middle, can be hard to look at a crowd and determine how many people are doing each, can be hard to see hands that are down because of people standing in the way.

By asking yes or no (or any question with a binary response), you cut down on the amount of discussion needed. Thinking about the different issues related to the topic and asking a series of binary questions can be useful to get a sense of how the group feels really quickly. It can also be useful to check in with one or two people who indicated that they disagreed so that at least they can feel heard and hopefully be less frustrated.

Comparison between the processes

Below is a table allowing comparison of these three different decision-making processes - Fist to Five, temperature check, and majority voting. The table outlines their details and relative speed to aid you in choosing the right process for a given decision making scenario.

| Fist to Five | Majority Voting | Temperature Check | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of response options | 6 (see section above) | 3 (yes, no, abstain) | 4 (Agree, not sure, disagree, abstain) |

| Speed | Medium | Faster | Fast |

| Strength | Allows people to give more nuanced responses & allows proposals to be adjusted into something everyone can live with, rather than just rejected | Quick & can be used when there are several options available | Quick & can be used when there are several options available |

| Weakness | Slightly more complicated so will take more time to explain | Many people may be frustrated | Can be ambiguous what hands that are at chest height mean |

How do I know what process to use?

There are many different aspects of the decision that may influence which process you want to use. The key ones are:

- Is the decision urgent? We’ve provided some fast versions above, but you will have to use your intuition to decide what’s the best way to balance discussion and speed.

- Is the set of options clear? See below on brainstorming if there are no options. If there are several you could do a majority vote to choose the most popular option and then do consent decision making to ensure it’s something everyone can live with.

- How contentious is the topic? Are there a lot of feelings? Best to discuss it thoroughly. As stated above, people usually accept a decision when they feel what they care about has been heard and the process is fair, so it’s worth slowing things down and hearing from people when tensions are running high. A round of hearing from everyone is always a good idea in tricky situations, make sure it stays as a round though and doesn’t become a discussion.

- How consequential is it? For example, are we considering moving to the shade to hold the People’s Assembly or deciding on an action that will trap MPS in their offices for days? This greatly determines the decision making process you’ll want to use. Moving to the shade can be decided by a vote or temperature check and no one will be that upset. A very spicy action will need strong agreement with lots of time to hear dissent and seek advice and feedback from those with expertise.

- Does it affect a large number of people? If yes, have you got their input? This is tricky because high profile, spicy actions in some ways affect everyone in the movement. We recommend reminding people that the Principles & Values and the Rebel Agreement are what we have to guide behaviour and that people have the autonomy to make their own decisions within those parameters.

- Who’s best equipped to make the decision? If there’s a person or a small group with the information and knowledge to make the decision and you trust them, why not let them make the decision? The group could share some thoughts with them and then leave them to it. Remind people that sometimes it’s OK that some people have their say and others don’t, because it might be an issue that person cares about in particular while everyone else doesn’t care (e.g., a focus on health and safety, or a focus on fairness).

- Can it be trialled for a period of time? Or is it a one off event? If it can be trialled, ask those with concerns to give it a go with the knowledge it can be changed in a day or two if they still have concerns.

Rapid Decision Making: As a facilitator, you generally don’t want to bring too much of your own input to discussions. But when a decision needs to be made rapidly (usually in a “the police are here and we need to do something quickly” context), facilitators can be quite active in suggesting what to do. So don’t be afraid to make a proposal, ideally by summarising the opinion that has been voiced most frequently and turning it into a proposal. Or after a temperature check on 2-3 proposals you have in mind.

What if I don’t have a proposal?

Some different options to generate ideas include:

- Ask if anyone has a suggestion (and ask them to be brief) and ask the group to use wavy hands to signal what ideas they like. Capture them all somewhere so everyone can see if possible. Do a decision making process above on the idea that got the most wavy hands. Best to set a time limit on this.

- People’s Assemblies are great for generating many different ideas because people have the chance to discuss in small groups and may be more comfortable sharing wacky ideas. Again, watch the group to see what ideas get the most wavy hands and pick that one.

- Negative Brainstorm: pose the question in the opposite form, e.g., what action do we not want to do today? This will take some time.

- Even though you’re the facilitator, don’t be afraid to suggest a proposal if you have one.

What if there are several options?

Are the options mutually exclusive? Could the options be combined? Remember, you may not need the perfect option, but an option that is good enough. If all your options are good enough then see what elements of them could be combined, but it is possibly more important to simply start taking action on one of them. In this situation, if you are stretched thinly, maybe the key criteria is which option will take the least of your limited capacity, or which can be delegated to a volunteer or temporary team.

Keeping track of the different options is essential, but can be difficult, especially when there’s many different variations of the same option. Visual aids can help such as writing it down and labelling them plan A, etc. Although if you refer to it as “Plan A” make sure you’re all on the same page about the plan you’re talking about. Then get people to vote so that you can narrow down the options and explore the top 2 further. Also, consider 'unpacking' exactly what people mean by specific words.

Try asking people to vote for each proposal and use consent based decision making to make sure it’s workable for everyone in the group.

Keeping it Smooth

A good facilitator can help keep the group on track to making a decision that works for everyone in the group. Encourage people to come to the meeting with all the information they need to make a decision. Point out logical fallacies (e.g., “those options are mutually exclusive”) and correct information when you notice it.

Information: Rebellions can be hot beds for rumours. Tensions can run high, people can be on edge which leads to exaggeration, especially when information is being relayed through multiple people. For example, the police changing shift can lead people to jump to conclusions that they are trying to clear the site. Fact check information and don’t share it unless it is from someone you trust personally or you’ve witnessed it directly. As a facilitator, remind the group to make decisions based on the best evidence available rather than hearsay.

Dissent: It’s your job as facilitator to ensure that everyone in the group can share their thoughts, especially the voice of doubt or concern that will probably make the proposal more robust. You can decide to set the threshold for dissent really high (“Does anyone have any major concerns with this proposal?”) or really low (“Does anyone have any little grumblings with this proposal?”). If there are people who you think might have a hard time speaking up, you can set the threshold lower for them. You may also model some dissent yourself so people feel comfortable saying theirs.

External factors make the decision for you: Make sure that the decision being discussed is not already decided by an external factor. For example, during one people’s assembly during a rebellion people spent a long time deciding whether to hold a road overnight or not. Half way through the People’s Assembly, someone asked “Who here is actually willing to sleep in the road tonight?” Two people put up their hands, and so the decision was pointless because there were not enough people willing to do the proposed option.

The key thing here is that if there is work to be done, check that enough people are willing to do it and they are heard on the issue. This should be done during the fact finding stage before you start the decision making process.

Other external factors could be that if we don’t act this minute, the police make the decision for you, so that limits you to choosing options already on the table.

Polar collaboration: Ask those who feel strongly about the issue to work together outside of the meeting and come back to the group with something that works for them. This is useful when there’s a few that care and others that don’t and it saves the latter sitting through those who care thrashing out the details.

Discouraging unnecessary permission seeking: Sometimes people bring a decision to the group that they can actually make themselves because it’s in their role description/mandate. Check whether the decision needs to be made by the group or whether that person can make the decision by themselves - they may still want to hear advice from the group. You don't have to know the mandates exactly, but use your judgement and if in doubt just ask "Are you sure you need a group decision/input on this? Is it a decision you can make within your mandate?"

Amplify: When someone from a traditionally marginalised background makes a contribution it can often be overlooked or repeated by someone else who takes the credit. Accrediting the originator of the idea with their idea can be really helpful to make sure the idea nor the person doesn’t get overlooked. Some facilitators highlight that they are not being strictly fair when it comes to young people for example. They take their points/questions more often and give them more time to speak, and publicly acknowledge that they are doing it and why.

Facilitation leadership: Facilitation leadership is helping the team achieve their purpose and ensuring everyone can contribute so the team can harness its collective wisdom.

Consistency: Although it’s great to rotate representatives and leaders, on the time scale of a rebellion, it can lead to a lack of consistency in who is turning up to meetings and so there’s no capacity to get to know each other and build trust. You could encourage the representatives that do come to site meetings to show up consistently.

Preparing to facilitate: As a facilitator, you need to bring groundedness, fairness, sensitivity to emotions, and wisdom. Yes, that’s a very tall order! If you are to facilitate, try to find some quiet time beforehand to relax a little, look after your needs and ground yourself so you can stay cool and collected and help others do it too.

Framing questions: The direction in which a proposal is made, e.g., "the proposal is that we leave the road" vs "the proposal is that we stay here", can influence the outcome of the decision. People tend to agree with questions and no one wants to be the naysayer (or at least it can be difficult to speak up sometimes), so people will probably tend towards passing the decision. That means you’re more likely to stay if the proposal is that we stay where you are, and more likely to go if the proposal is to leave. There’s not much that can be done here because there’s no neutral framing in this example, but it’s something to be aware of.

Acknowledgement: This text is derived from an earlier document, Guide to Decision Making on the Streets.