Fin-ancialisation 🦈

Water - a Cash Spiggot for Investers

How did we get here? What does it mean?

A brief history of ownership of water companies in the UK

From the late nineteenth century onwards, water services in England and Wales followed a pattern similar to most European countries. Water services were owned by a mixed bag of local authorities, with some individual authorities running water companies, some large inter-municipal operators, and a surviving handful of private water-supply only companies, which were strictly regulated by a simple cap on their profits at a maximum rate of return of 5%.

In 1974 the service was reorganised. 10 unitary regional water authorities (RWAs) were created, each covering a river basin area, each responsible for water quality, water supply and sewage treatment. These authorities were appointed by the government, not by municipalities, and so were not accountable to local government any more. The RWAs reduced the number of employees from 80,000 to 50,000 between 1974 and 1989.

Management and Control by Economics, Not the Science

The Thatcher government originally proposed water privatisation in England and Wales in 1984, but due to strong public opposition the proposals were abandoned before the issue could influence the 1987 election. Once this was won, the privatisation plan was resurrected and implemented rapidly.

Under the Water Act 1988, the newly formed water companies became owners of the entire water system and all assets of the Regional Water Authorities (RWA's) in England and Wales. The RWAs were sold by issuing shares on the stock market.

The exceptions to the privatised for profit of the shareholders model are in Scotland and Northern Ireland, however, water remains controlled and operated by public authorities. In Wales, Welsh Water (Dwr Cymru), the business is a not for profit, albeit the Board has received massive bonuses on top of high salaries, despite shocking performance on sewage pollution.

Contrary to promises by the politicians, privatisation did not create any competition and resulting lowering of bills for consumers. The companies were given monopolies in their regions for 25 years, without having to compete even once for the business. Nevertheless, the government was desperate to mark the sale of common assets to private owners a success.

Behind the scenes, however, there was an injection of welfare into water companies. The government wrote off all the debts of the water companies before privatisation, worth over £5 billion pounds and gave the companies an additional ‘green dowry’ of £1.6 billion from the public purse, i.e. taxpayers.

The initial water pricing regime, set by the government, resulted in pre-tax profits of the ten water companies to rise by 147% between 1990/91 to 1997/98 with sewerage and water prices rising respectively by 42% and 36%. The companies were also given special exemption from paying taxes on profits.

Who Watches the Water Workings?

OFWAT, the financial regulator for private water companies, is statutorily responsible for ensuring that the companies were profitable. It has performed that supporting role very well; it's also responsible for encouraging efficiency. As there is no competition, however, OFWAT compares the companies' performance with each other. That would be the equivalent of a low watermark!

Water companies were protected from takeover for 5 years by the government’s ‘golden share’. Once the 5 year period was up, many were bought off the stock market by giant multinationals. These corporations restructured, stripped and mortgaged and then resold for huge profit, a process commonly known as 'financialisation'. A process in which making profits from financial constructs, becomes more profitable than trading real products and services.

To learn more about the neo-liberal economic theory behind financialisation, be sure to check out Investopedia's explanations of eg 'asset stripping', 'value extraction', 'derisking finance'

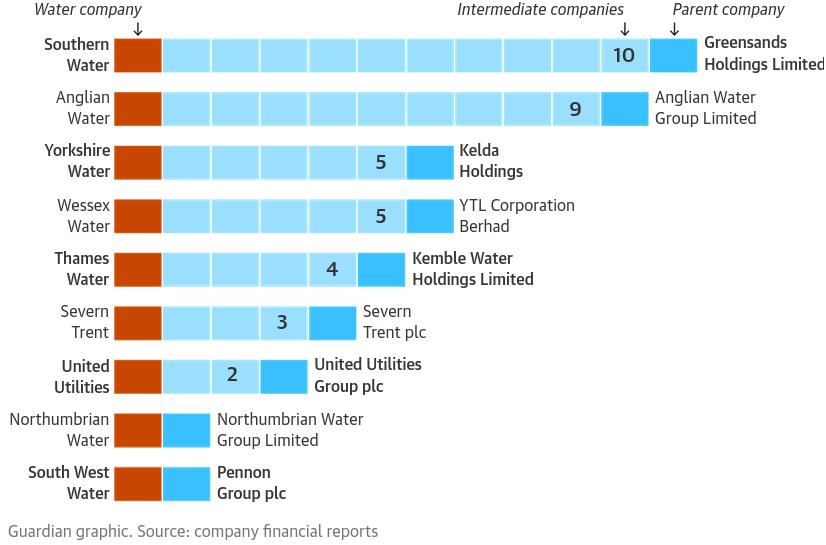

The increasing financial engineering for shareholder profits leads to more and more opaque and complex ownership structures. Check out this Guardian graphic showing the structures for English water companies:

Read more about transparency and accountability problems with the financialisation of water.

Case Study in Failure: Thames Water

The result of financialisaton is best demonstrated by looking at a specific example:

Thames Water Ltd - Europe's largest Water and Sewerage company.

- 1974 - The Thames Water Authority was formed as the largest regional water authority in the UK.

- 1989 - Thatcher's privatisation handed all water system and assets of the region to Thames Water Ltd, free of debt and a 'green dowry' gift of more than £100 million.

- 2001 - RWE, a German energy giant bought Thames Water off the stock market and burdens the company with a £3.4 billion 'mortgage' debt.

- 2006 - Macquarie Group, an Australian global financial services group buys Thames Water for £8 billion.

- In the next eleven years Macquarie Group adds another £7.1 billion 'mortgage' debt to the company while paying themselves £2.8 billion in dividends. Over this time Macquarie sells off Thames Water in chunks to the highest bidder.

- 2017 - Macquarie successfully sold all Thames Water shares at healthy profit for themselves. Two thirds of Thames water is now owned by pension funds in different parts of the world.

- Over the last 35 years in private ownership Thames Water has paid out over £7 billion in dividends to shareholders and accumulated a debt of over £15 billion. Every month Thames Water customers pay approx. 20% of their water bill just to pay the interest on this debt.

- 2024 - Thames Water is now in existential crisis and may soon collapse under its burden of debt.

- The company has asked to be allowed to rise bills by 50% and begged OFWAT to be lenient with future fines for illegal behaviour.

- Thames water demonstrates how privatisation turned water, the essence of life, into cash machines for globally capitalised cooperations.

- Thames Water's ruin is but one example of the terrible consequences of the financialisaton of water while underinvesting in real and badly needed infrastructure.

- The resulting broken sewage systems are intolerable for all life in our land and coastal waters.

- We must correct this mess now. Different models and ways of funding are available. It’s time for the people to have their say.

For an informative potted history of Thames Water as a case study in how the neo-liberalism works, CronxWatch is worth a listen to gain an insight into how financialisation tools work this essential utility for the interests of the few!

Sources and Further Learning:

- How infrastructure building projects become assets which profit water companies at the cost of customers and what the alternatives could be - Alternatives to Massive Infrastructure:

- How Privatisation has failed: "Despite its deliberate limitations, the Cunliffe Review still manages isolated admissions of privatisation’s failure, noting how “high levels of debt relative to equity have impaired resilience” – a polite understatement for decades of corporate looting disguised as financial innovation."

- Why Public ownership (at least initially during transfer of assets) costs nothing..

- Academic Research: 1989-2001 UK water privatisation.

- Wikipedia on Water privatisation in England and Wales.

- Parliamentlive.tv: Industry and Regulators Committee.

- 'The Guardian' links:

- How Privatisation Drained Thames Waters Coffers.

- Thames Water's Second Largest Investor Slashes Value of its Stake.

- Thames Water Nationalised Ofwat MPs Customers.

Definitions: for an explanation of finance terminology or acronyms search Investopedia.